Designing a New Old Home series, Table of Contents

Beginnings — Why an “old” home, and how we came to buy land

Curiosity — Advice on starting

Research, Sketch, Collect — Essential research for home design

Defining Constraints — What can we do without

The Elements ← You are here

Materials and Hardware — What we built with

The Studio

The Kitchen

…

The Elements: Heating and Cooling and Airflow

Ensuring your house works well with the natural world is one of the most crucial parts of designing a home. Like I wrote in the first part, it’s also one of the most ignored. We wanted to build a house that would stay as naturally cool in the summer as possible. If we were successful, we wouldn’t need air conditioning. We also hoped to take advantage of modern insulation to mostly heat the house with a medium size wood stove, and avoid any forced-air duct work.

Ceiling Height

Heat rises. Tall ceilings have two thermal effects: In the summer they keep the house naturally cooler, but they also make winter heating bills larger because you have more interior volume to heat. If you have air conditioning, tall ceilings lose the first benefit, since total air volume makes the AC cooling more costly. Insulation used to be poor, and heating expensive, so many of the oldest small houses in New England (and other cold climates) have low ceilings. Lots of old southern architecture has taller ceilings, by contrast.

While some New England homes would have ceilings no taller than a door, more opulent homes (often heated by wood or coal-fired furnaces in the basement) might have taller (9–12 foot) ceilings. Among historic homes in New Hampshire you can find many examples of both. As far as houses built in the last 100 years, the most common ceiling height is about 8 feet.

We’d rather have cooler summer temperatures and more light, and we dislike the cramped feel of lower ceilings, so we decided on 9 feet for the first floor, and 8½ feet upstairs. Modern insulation works very well—better than I imagined actually, I spent most of my life in an 1840’s house—so heating the space has not been a problem. We collected examples of older houses in our footprint (30x38 feet, colonial style) with 9-foot ceilings to ensure we weren’t doing anything that would look uncanny. In general, the smaller the room, the more a tall ceiling begins to make the space feel oddly cavernous, so the slightly shorter ceilings upstairs help with a more cozy aspect ratio for the bedrooms.

There’s a lot more to ceiling height, and to what height feels “right”, but its somewhat climate and space specific. Both Get Your House Right and A Pattern Language offer more useful advice there. As I said before I encourage you to find out why, whenever possible, people in your area built traditional homes the way they did.

Cooling (Airflow)

We weren’t planning on having central air conditioning, so we investigated a few passive options for cooling:

A porch to block the summer sun (Not in the budget! But this is worth investigating for your own project, and we may build one some day.)

Trees with foliage to block sun (Some day, but not with our new construction.)

Taller ceilings (check)

Paint the house white (check)

Airflow, discussed here:

You should seriously consider if you want central air or not, and how much you want. It’s taken as a default in new construction because duct-work everywhere is taken as a default. I think people today overdo it, especially in temperate climates like New Hampshire, where cooling just a few key rooms would be simpler and cheaper.

The other complication with central air can be inferred here, with these bedrooms in a home the next town over that sold (inexplicably) for 2 million. See how they’re on the ceiling?

There are no photos of the attic from this listing, and the reason is most likely because the space has become a total waste. Often in order to put in these vents, the attics will look like this:

In other words, central air can make floor plans more complicated. If you find awkward geometries and bump-outs in modern construction, it’s almost always some duct-work. And these complications can destroy otherwise-usable space, most usually the attic or final story.

Having central air via ducting changes how you use your home. There are fewer reasons to open windows, so people open fewer windows. (In newer office buildings the somewhat crazy result is that you cannot open the windows.) As people open the windows less, they air out the house less, and are perhaps at more risk of indoor CO2 buildup, and the buildup of other gasses like formaldehyde, which unfortunately outgasses from a lot of modern construction materials and furniture.

I’m skeptical of forced-air heating and cooling systems for other reasons. Careless designs can lead to poor use of space, poor performance, and difficulty keeping them clean, which can lead to mold and other respiratory issues. Most people agree that radiant heat feels better (people complaining of dry skin in the winter are often in part complaining about dry forced air heating, and don’t know it), and radiators can warm rooms more evenly than forced air ducting.

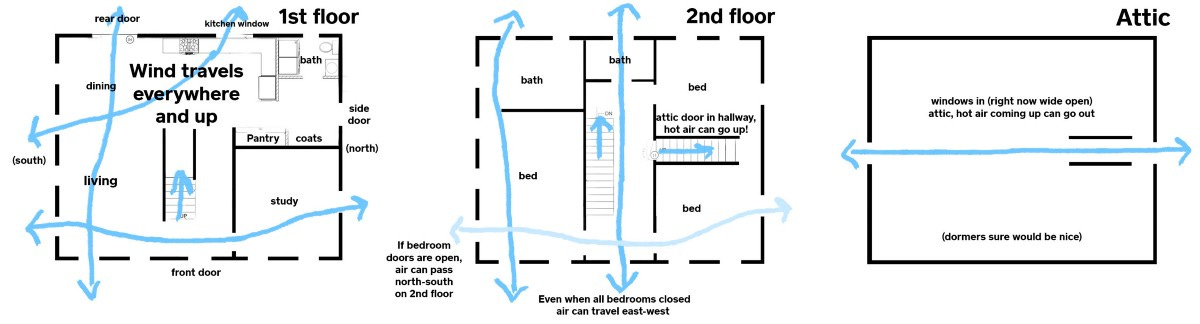

We decided on radiant forced hot water for our heating system, and several considerations for natural cooling, including incorporating as much passive airflow as possible. Ideally, we wanted wind passage north-south, east-west, and of course upwards. In our design, the downstairs is somewhat open, and the upstairs hallway affords air passage with opposite windows. We then put the attic stairs in the middle of the 2nd floor hallway, so air could continue escaping upwards.

From the outside:

The house sits on a slight hill, which may also help with airflow, as the hill compresses wind. This effect is stronger on bigger and more isolated hills, which is why windmills are often placed on ridges. I’m not certain this helps with interior airflow, but the wind from the hill definitely helps keep bugs off the back patio.

Aside: In the back of the house, note the white vent pipe and chrome base of the black chimney. I wish these were painted black or dark gray, and should have asked for them. Never assume a contractor will know what you want or make any aesthetic decisions on their own! Their job is to install stuff, your job is to think about what looks good, and then ask for it.

Air passage on the inside:

The idea is simple: Let air across, and let it upwards. The house is open enough (especially when bedroom doors are open on the 2nd floor) that wind can move quite freely through. Note also how the attic door is placed centrally on the 2nd floor, so we can keep it open for hot air to travel upwards.

Another aside: From what I knew of airflow and ancient designs, it seems obvious that the cupola in many buildings was originally meant to collect and then release rising hot air. It’s too bad that cupolas in modern houses are usually not accessible enough for the air to get to, and often have totally sealed windows or shutters. In this old 1840’s house (my childhood home), the cupola access inside was well placed to collect hot air and have it blown away. Unfortunately, we never opened its windows, so I don’t know how well it would work.

For our house, the combination of natural ventilation and tall ceilings works well on most days. Thanks to modern insulation, when the days are warm and the nights are cooler, it easily stays cool all day as long as we close the windows in the morning and open them again at night. It works so well that several visitors have thought we had AC.

There are a couple hot stretches of summer where we would have liked to have AC, but it was manageable. This setup may work even better with a whole-house fan, but we don’t have one. When our first child was born (July 2020), we did end up buying a plug-in mobile AC. We use it a few days a year now by putting it in the upstairs hallway.

If you’re on the fence I think its worth considering air conditioning only on the second floor, since it gets hotter, or better yet only in the bedrooms. Many people effectively do that here simply by getting a window AC units, but central air does have the benefit of being significantly quieter indoors. With a little more budget and foresight, and a much longer planning phase, I think we would have gone the bedroom-only route.

Heating Systems

The underlying heat for our house is radiant forced hot water. In NH it’s common to have (heating) oil for heat and propane for cooking, but we wanted to keep systems simple and use propane for both. The major downside is installing a large propane tank, and in some areas propane is more expensive, but it’s otherwise preferable to heating oil. I wish we had a steam system like in very old houses, instead of forced hot water, but designing one into our house would have increased cost and time.

Aside: In the New Hampshire countryside power outages of a few hours to a few days are not uncommon in the winter. This is partly due to being the second-most forested state, after Maine. Heavy snow or ice on weak tree branches can break a lot of power lines. The old single-pipe steam systems, which I grew up with, are a very elegant invention, and can potentially be run even when the power is out. With forced hot water, power is essential to run the pumps that circulate the water from the boiler, so you need a generator if you want to use it when the power goes out. But we were not worried about heating through power outages because our wood heating also requires no power.

We wanted as much of the house as possible to be heated by a single wood stove. As I mentioned earlier, we also didn’t want a very open design. We prefer discrete rooms, they offer more privacy, more quiet, and more opportunities to make the home feel cozy. It’s much harder to decorate big tracts of open space, and much harder to furnish those spaces into patterns like a breakfast nook, a comfy reading/sitting area, and so on.

Before the 1500’s, open floor plan houses were mostly a necessity. The entire house was heated by one fireplace, which doubled as the stove, called the hearth. As time went on, richer houses gained additional fireplaces, and rooms multiplied (and the concept of a manor’s “great hall” gave way to hallways, which were a late 1500’s invention). Today its very easy to build well-heated rooms throughout the home, unless you’re like us and still want to heat with a wood stove. Despite not being a necessity, open-concept floor-plans are somewhat popular. I think this is partly due to laziness, partly to being an easy way to make smaller spaces feel bigger, and partly because builders think that’s what people want.

In designing your own house, you should think hard about just how open you want things to be. Think about your needs, your activities, and the activities of everyone else in your (future) family. Where will the kids play? Where will you read? Eat? Are people going to watch TV? Where will you be when you are trying to concentrate on something? Are they all the same one big room? I hope you get the idea.

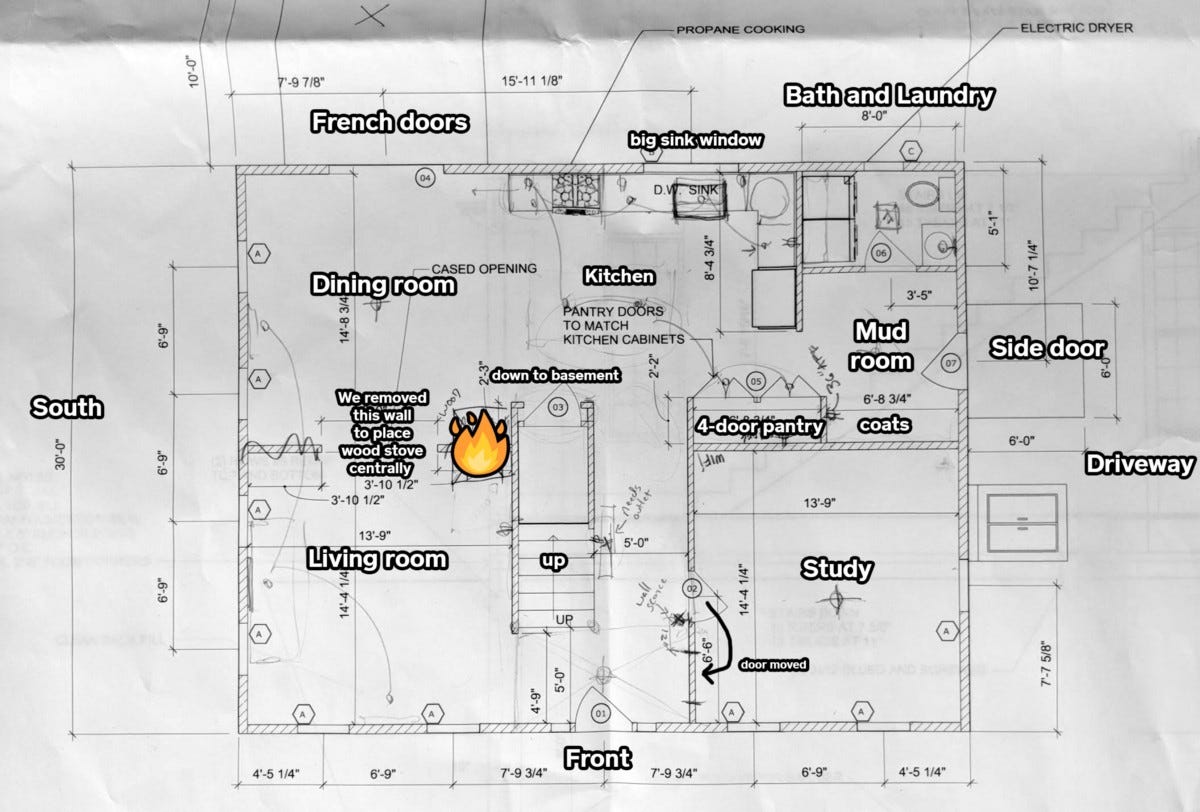

All of this is to say: We originally wanted a wall between the dining and living rooms, as seen below, but then we couldn’t decide on an ideal place for a wood stove. This indecision went on even after we broke ground. Eventually, we decided to axe the wall and put the wood stove in the middle, between the rooms:

Does it work?

The medium-sized wood stove we bought, a Vermont Castings Encore, is enough to nearly heat the entire house. It can easily bring the downstairs to 70° (21° C), except the study, and it heats the master bedroom too (above the living room). The two north bedrooms are colder, and also on a separate heating zone, so those require some propane-powered forced hot-water heating at night if occupied.

Downstairs, the thermostat is permanently set to 55 degrees (12.8° C). In the winter, as the night’s fire dies, the temperature will drop several degrees by morning, though it may not get to 55 unless its very cold outside.. Then each morning we get up and start a new fire (using yesterday’s embers if we were up late) to heat the house. Of course if this sounds unappealing to you but you still want a wood stove, you can always set the thermostat a lot higher than 55.

The cold start to winter mornings has become one of my favorite things about our house. It causes us to wake up and start the day much earlier. Before, I would get up with little time to spare and rush off to work. Since we moved in, we wake up early to restart the fire and make coffee. Sometimes Simi will write, or we will both read, or talk, but often we just sit together for a while and slowly wake up. When you have 1–2 hours in the morning where you can dwell calmly, drinking coffee, and not hurrying, you feel ten times better. We tend to continue this routine into the summer, waking up even earlier with the sun, and keep the coffee pot with a few candles instead of the wood stove.

Having children has changed this routine a little. It’s a good deal more variable contending with the needs of a 2-year-old and newborn, but the idea is the same. We might read to Luca instead of ourselves, or he might play with blocks while we sit together. And he always wants to be involved in the cofee-making.

~ ~ ~

Next times

Light is the other underserved natural element of home design, almost ignored in modern designs in favor of electric lighting. The topic is too big for this post, so it will get it’s own a little later. In the next post we’ll go over materials and hardware, so maybe Light will come after that.

This newsletter is called The Map Is Mostly Water, and is about a number of topics.

This house design post is part of a series inside that newsletter, called Everyday Aesthetics.

If you enjoy my writing, please consider supporting this newsletter.

Having spent a lot of time in ‘the boreal’, and as a consequence (way too much) time in snow-holes …

They ‘work’ only due to the knowledge, not that “hot air rises” but, that “cold air sinks” (you sleep on a raised platform, with a ‘sink’ to allow the cold air to move away and air circulation to occur).

Just an aspect I thought you might consider (and that never gets included in modern house design, which spend inordinate amounts of time/effort/money on heating air, but seem to forget about where all that cold air goes to).

Counter-intuitively, most of the oldest homes here, whilst obviously being unable to totally exclude ‘drafts’ (windows, fire-place/chimney, etc.), have ‘intentional’ gaps at the (bottom of) doors that modern sensibilities/knowledge insist on blocking … until they realise it actually makes the home colder (qualifier; they allow cold air egress, but not free air-flow, due to 'air-lock' porches).

That and the predictable rise of auto-immune respiratory issues from living in hermetically sealed homes, re-breathing’ all the gunk, is my excuse for not doing all the ‘upgrades’ SDWMBO demands (it’s a good one, and I’m sticking to it).

Thanks a lot for sharing this, super appreciated. I love wood stoves, and have been thinking about picking one up for our house. The Vermont Castings Encore you've got looks gorgeous. I'm not sure if it's a loaded question, but what's your take on the pollution question of them...? Newer ones like the Vermont seems a lot better than older alternatives in that regard.