What is Good Within Social Networks

What outward form and feature are He guesseth but in part; But what within is good and fair He seeth with the heart.Samuel Taylor Coleridge: To a Lady, Offended by a Sportive Observation

I think we are still in the early days of social networks. We are only just beginning to figure them out. We certainly underestimate how positive and useful they can be, partly from a careless pessimism, and partly because the owners of major social networks seem to lack vision. Despite a few models enjoying success (at least, perpetuation), there seems to be little overt thinking about the nature of social networks and how to improve them.

Let’s scratch the surface.

~ ~ ~

There are some instantly recognizable functions of social networks: Famous people want a platform. Common people want something like TV 3.0. Or sometimes they want the possibility of becoming famous themselves. These are perfectly fine, but by themselves these functions just approximate the mass media that came before.

Then there are the social parts: Not the broadcasting and viewing, but the replies and direct messages. One should take care to appreciate, from a historical perspective, that these are very unusual.

I have mentioned before that knowledge in pre-modern times was transmitted person-to-person. The inventions of the printing press, radio, and TV changed that quite drastically over a few hundred years. Unlike the time of Aristotle or Da Vinci, every person today will read, watch, and listen to more recordings of people than they might ever talk to. Knowledge and culture transmission went from a focus on conversation (everyone talking to everyone) to recorded media (everyone watching or reading an extremely tiny handful of people). Crucially, as much as some might try, there is no talking back to your TV.

Social media lets you talk back. Social media comments resurrect dialogue’s benefits of doubt, follow-up, clarification, collaboration, contradiction, and so on*, and in a very public way. Social networks are a new paradigm compared to broadcast media, yet the technology recaptures something ancient. Used well, they re-insert the agora into public life.

Albeit, with a somewhat different scale!

But it is a mistake to think of social media generally as throwing all your thoughts to millions of people, the supermassive marketplace of ideas. In practice, the vast majority of people reach, and are looking for, a town-sized agora. We can restate the features then: Famous people want a platform, common people want a new TV, and much of the middle want their own little burrow. And sometimes they find it.

* part of the problem with (infamously) poor behavior on social networks is that—by relying on broadcast media more and more over the centuries—we may have let these conversational skills atrophy a little too much. It has always struck me how in much older literature such as Sir Gawain and The Green Knight (1300’s), one of the virtues emphasized over and over is being exceptional at conversation.

~ ~ ~

There’s a common complaint that modern life seems to make friendship more difficult. I think this is partly because friendship is often created by consistent, repeated small interactions with people in unplanned settings, and we have fewer of those than ever. The car and the department store and online ordering erased many of these social settings—even though we might not have thought of the butcher as a social setting. The decline of clubs, fraternal orders, churches, etc., also played a now-lost role.

Social networks here are again a powerful technology: They claw back for each of us space for small, unplanned interactions. Repeatedly showing up to the agora has the effect of meeting other familiars. They are how many people make friends and professional contacts, to say nothing of other stripes and collaborations. People sometimes joke that “Twitter is a dating app” — and they’re right. It is even how the richest man in the world met his girlfriend. This isn’t a feature that was planned into some social networks, instead it is a function of creating a space where people can see and be seen.

It is with an eye to these things that I think about social networks, and treat them like the agora that they are. To me other people bemoaning “doom-scrolling” or that some social network is terrible seem to be lost in another part of the forest, and not a good one. But it is up to them to get out. And it is up to the creators of social networks to recognize the good parts and build on them.

Between Public and Private

The best features of many social networks are not the public or private spaces they offer, but the ability to carve out something in between. To create what might be called intimate spaces.

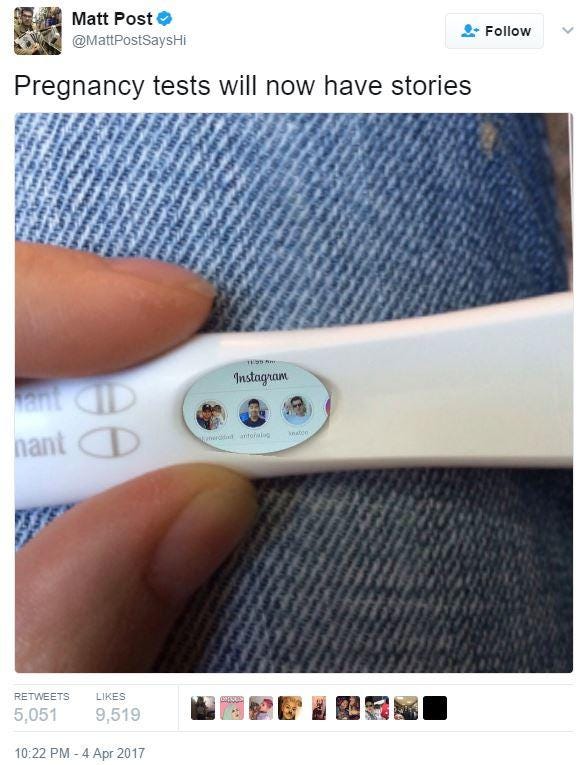

An obvious example: Snapchat solidified the idea of a “Story”, a format that Instagram copied and then ported to Facebook, prompting a lot of memes that we would soon have them everywhere:

(While this post was a draft, even Signal, the neither-very-public, nor-very-social messaging app, has introduced a stories feature.)

The simplest format of social media involves creating public posts and receiving public replies. With Stories, you make one or several public disappearing posts (gone after 24 hours), which beckons you to be a little less formal, and then instead of commenting, one can only reply to the story-maker directly. Public posting, private replies.

The reason the format worked so well—and why companies wanted to copy it—is that Snapchat stumbled upon a format that is a perfect avenue to intimacy. The ephemeral posting lowered expectations around formality. The normalization of private replies to public posting encouraged conversations to happen instead of comments. Before, direct messaging someone might have been unusual, now it was normal. Friendship is consistent, repeated small interactions with people in unplanned settings. Now we have them. People have met spouses through Instagram stories! If some ancient tale of romance was set in present day, there’s a zero percent chance they would meet in a dating app, those most unromantic of atmospheres. But they might have crossed paths on Instagram or Twitter.

I would think we should expect social networks to spend a lot more time thinking about why certain features are so compelling, or this space between public and private, or how to make new spaces. Externally, especially looking at features added to the major social networks in the last few years (stories excepted), it just doesn’t seem to be there.

It is easy in a lot of ways to see what the best social network is in one way or another. Twitter may be the most intellectual social network, and possibly one of the best for making friends, because many of the features encourage carrying and multiplying conversations, and crossing the public-private barrier. But this title is almost completely incidental, the company didn’t set out to create an intellectual sphere, and many of its best features were “discovered” by users rather than planned. Hashtags, quote tweets, and 280 character limit were all the result of users trying to use the platform in a specific way, and the engineering team recognizing that and leaning in to them. Sadly Twitter takes such cues rarely.

I think the future of social networks is more compelling and understudied than some of these companies seem to think themselves. Perhaps that’s just arrogance on my part. Either way I am optimistic — I really do think we are in the early days.

~ ~ ~

Substack

The company that is thinking the hardest about social networks might be the one you’re looking at right now.

Newsletters are a one-to-many medium, though with email and comments both private and public replies are possible. But thinking of Substack as just an email platform or even a newsletter platform is a mistake. It’s becoming clear that their interest lay not just in mass distribution but in the social part of social network.

Instead of looking to reproduce a (say, Twitter-like) purely public sphere or private email list, Substack is aiming squarely for the intimate spaces in between. With the right tools, every large Substack can become a small agora of its own. The introduction of Substack Chat — described first as a dedicated space for more casual interactions, and later as a place to have group conversations with subscribers — fits perfectly into this.

As each Substack goes from being a newsletter to a community, the result is not one large social network like we’re used to, but an archipelago consisting of a million smaller ones. And if those have the right tools, and the islands can be loosely stitched together or traversed from time to time, the result will be a true network that is both discoverable and intimate. It is clear to me that Substack is doing what it can to build these tools. Features like like coauthors, and recently mentions and cross-posts are to foster the cross-pollination needed to break out of individual subscriber silos.

I’m quite interested in the evolution here, and with Chat in particular. After speaking to some people at Substack, I suspect it is so nascent that the name will be in some measure a misnomer. They know that we are in the early days of social networks.

Dear Reader,

When I started this newsletter in 2020, long before I had any notoriety on Twitter or anywhere else, I called it a stromata — a patchwork of anecdotes, fables, tales, advice if you ask for it, photography, questions, sentiments, long distance thoughts, and ways to get lost in the forest. I suspected that it would simply be too disjointed to keep much attention; I simply wanted to think out loud.

I am surprised by the response. Though it is my nature to be surprised by everything, I would not have expected ten thousand subscribers to eventually show up.

In the near future I look forward to hearing from some of you on Chat, and learning who you are. I will probably also use Chat to share a few more informal things, including unedited thoughts and some sources of inspiration as I find them among my days.

For now,

s s

~ ~ ~

notes:

“I have mentioned before…” — this paragraph is greatly summarizing an argument I made in Are We Still Thinking?, which can be considered my first post on the nature of social networks.

“…the richest man in the world met his girlfriend.” — Supposedly, Elon Musk made a tweet about Roccoco Basilisk in 2018, found that Grimes made the same joke a few years prior, and messaged her on Twitter, later attending the Met Gala together. Musk has since purchased Twitter.

The painting is “Hip, Hip, Hurrah!”, oil-on-canvas, 1888 by Peder Severin Krøyer.

You have successfully redirected my thinking about social media. There is also an asynchronous aspect to Substack commenting. Today someone liked a comment that I made over a year ago, which felt a little odd--like a long pause between saying something and having the other person respond. I was also reminded that the comments I make don't just disappear as they do when spoken.

Very useful piece Simon, and it certainly reflects my experience here on Substack. I have gotten to know--to befriend, really--a set of people who read my Substack. They comment, we email, and I’ve even had phone conversations with several of them. When I next visit England and France, I intend to lift a glass. That’s a beautiful thing. And also beautiful is that I often run into my “friends” in other neighborhoods, which is to say in the comments section of other ‘Stacks. More and more, I do find that the signal feature of Substack is the conversations.