Long Distance Thinking

THE TRUTH MUST DAZZLE GRADUALLY

OR EVERY MAN BE BLIND

— Emily Dickinson

The knowledge of a carpenter is in his hands. The apprentice must work with his own to discover it.

Here is some terrible advice: “If you can't explain it to a 6-year-old, you don't understand it yourself.” Typically attributed to Einstein, the phrase only became popular long after his death, around the new millennium. It is somewhat unsurprising that an age of shorter attention spans would give currency to such a quote. Present day we find ourselves at peak explain it to a six year old:

Many concepts can be explained concisely, in simple language, and we should all strive for clarity. But the aphorism is a mistake, for a number of thoughts approximate the carpenter’s craft, and to meaningfully reveal them requires time and attention. Sometimes these cannot simply be told to another at all, they must be grown. For a topical example, we know that maturity itself cannot be imparted to a six year old, no matter how good a summary we might give. Despite our understanding, we know it is something that can only come to each of us in time. This pattern is more common than we think. True things are disclosed slowly.

Articulating ideas as simply as possible is attractive, not least because getting people to agree with us is attractive. But we have a tendency to overrate ideas that can be shared easily, with the most apparent advantages. By constant simplifying, we may be lulled into abridging our own ideas a little too much, and sooner or later our audience—or ourselves—might come to expect only these truncated thoughts. What is easy to explain is not necessarily what is best. What is easy to understand is not necessarily what is true.

A practical example:

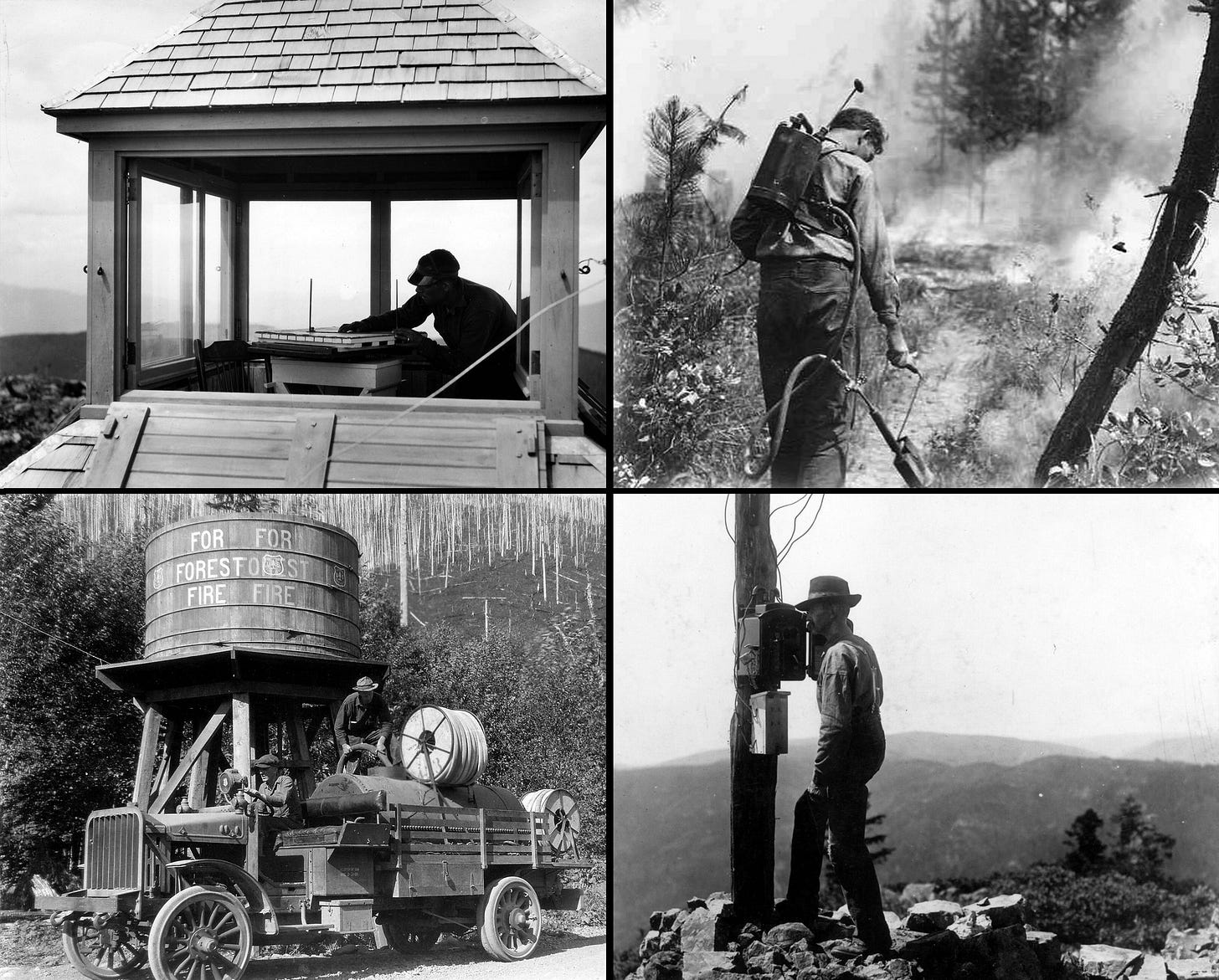

In the 1930’s, the US government saw an enormous opportunity. By leveraging the latest technologies, for the first time it seemed possible to extinguish even the smallest and remotest fires. The reasoning is easy to explain: Though it may take considerable resources, successfully locating and suppressing all fires early, even possibly harmless ones, will prevent large fires from ever forming, saving net resources. (Note that most of the concern at the time was centered around loss of timber stock for industry and national defense, and not about settlements burning down.)

Technologically armed to the teeth, aggressive firefighting policies quickly became the rule.

This firefighting policy came into serious question decades later. By the 1960s, it was apparent that no new giant sequoia had grown in California forests, because fire is an essential part of their lifecycle. Fires also had utility in timber production—they clear understory, allowing more valuable timber stock to grow. And in dry climates like the western United States, with an absence of fire, flammable material simply accumulates, creating more dangerous situations years later. As problems surfaced and compounded, in response, there has been a slow and experimental shift from fire fighting to fire management.

New technology enables new solutions. A quick thought becomes policy, which becomes a long disaster, which teaches us, at last, to think a little longer. It is right of us to call fire management an “experimental” policy, for we cannot make policy about the natural world as if it is a board game of rules and resources. We simply do not know all the rules. We can only intervene and wait for the surprising consequences we never predicted. Fire policy was an experiment all along, it was only ever a question of how much we were willing to assume at one time.

The archives of human cleverness are filled with blunders. When read in a good mood, history is a blooper reel. But it should not be lost on us that history never repeats, and modern technology enables ever more leverage. The more technology you can harness to commit an idea, and the faster your idea can spread, the greater the magnitude of something going wrong with a single decision. Scale is a capricious beast, one that becomes easier to summon and harder to predict. Be very careful when you let it in the house.

~ ~ ~

Now, there is a law written in the darkest of the Books of Life, and it is this: If you look at a thing nine hundred and ninety-nine times, you are perfectly safe; if you look at it the thousandth time, you are in frightful danger of seeing it for the first time.

— G.K. Chesterton

Philosophy begins in wonder, and the art of it is to keep this wonder with you. Many questions are worth asking, re-asking, revisiting, rethinking. One must seek Knowledge, but be a little wary of finding it. Perhaps excessive, but one could say the idea of possessing knowledge represents a kind of complacency. This is what Socrates meant: Once you think you know, you stop looking. You cease your wonder.

These letters are intended partly as a catalog of long distance thoughts. They are commentary on topics that cannot be conveyed compactly, that I ask aloud and re-ask in a number of ways. Some topics, I think, can only be approached this way. Scale is one of them, it is simply a topic too large, with too many sides, to see at once. You must come back to it often and continue to grasp at it. It will rear its head again.

More faint: If you read that which is unique breaks and about agency and my praise of the gods, and perhaps others, and read between the lines, you will find a thin thread that binds them. The thread vexes people, it manifests in different ways, and it doesn’t quite have a name. People grope at the topic, try to name, summarize, rationalize, even begin advocating ideologies and assigning blame. There is an intense desire to make it digestible. This PowerPoint-ification leads to all kinds of silly outcomes. Not all sources of light are worth staring at: Some summaries illuminate. Most obscure. Better to think a little longer, if you want to take the thread seriously.

There is a somewhat obvious term for long distance thinking: Contemplation. We pass over this word too quickly to really consider what it means. It has fallen out of favor, outside of the occasional raiding of a thesaurus. I find it interesting that even the definition of contemplate has suffered from over-summarizing. The first dictionary definition, in today’s Merriam-Webster:

To think deeply or carefully about (something)

I stopped to contemplate [=ponder] what might have happened.

He contemplated the meaning of the poem for a long time.

Life without them is too awful to contemplate. [=too awful to even think about]

Compare the brevity, and examples, to its first definition in Webster’s 1913 edition:

To look at on all sides or in all its bearings; to view or consider with continued attention; to regard with deliberate care; to meditate on; to study.

To love, at least contemplate and admire,

What I see excellent.

—MiltonWe thus dilate

Our spirits to the size of that they contemplate.

—Byron

And that same definition in Webster’s 1828 dictionary, his first edition:

To view or consider with continued attention; to study; to meditate on. This word expresses the attention of the mind, but sometimes in connection with that of the eyes; as, to contemplate the heavens. More generally, the act of the mind only is intended; as, to contemplate the wonders of redemption; to contemplate the state of the nation and its future prospects.

Language is a growing medium for thought, and here we witness something like soil compaction. Why? That nameless thread, it’s at work here, too.

(Aside: It is not only interesting how compacted the thinking has become, but how much of the spirit of an age is present in each work. Webster was deeply religious and nationalist, and considered his dictionary a project of “federal language”, a way to distinguish American language and thought from British. These shine through in his very personal 1828 definitions. The 1912 edition is interesting for using quotes from literature, with only last names, simply assuming the reader is familiar with them, or will know how to find them otherwise. The modern dictionary lacks confidence that the reader can fully parse the example sentences without some parentheticals.)

One way to tease out thinking is to create new language, so if I cannot say “contemplation” and be understood, I will say something else, and hope you consider it as I do.

There’s something closer to the carpenter’s craft that is required of long thoughts. Napoleon, who set up so many republics, kingdoms, and confederations, gave this mention (warning, lament), “A form of government that is not the result of a long sequence of shared experiences, efforts, and endeavors can never take root.” Civilization only exists at long distances, too.

The cure for over-summary, I think, is something akin to cultivation. States and maturity need good growing conditions and time. The wonder we should concern ourselves with: What else has been hidden by summary? What thoughts must we resist abridging? Those giant sequoias echo a reminder to ask ourselves, what are the unseen things today that could be growing?

Another time,

s s

~~~

p.s. “If you can't explain it to a 6-year-old, you don't understand it yourself.” — Another small disagreement, more implicit. You shouldn’t be so concerned about whether or not you understand something before you try to explain and share. Some things can only grow in the light of others.

~~~

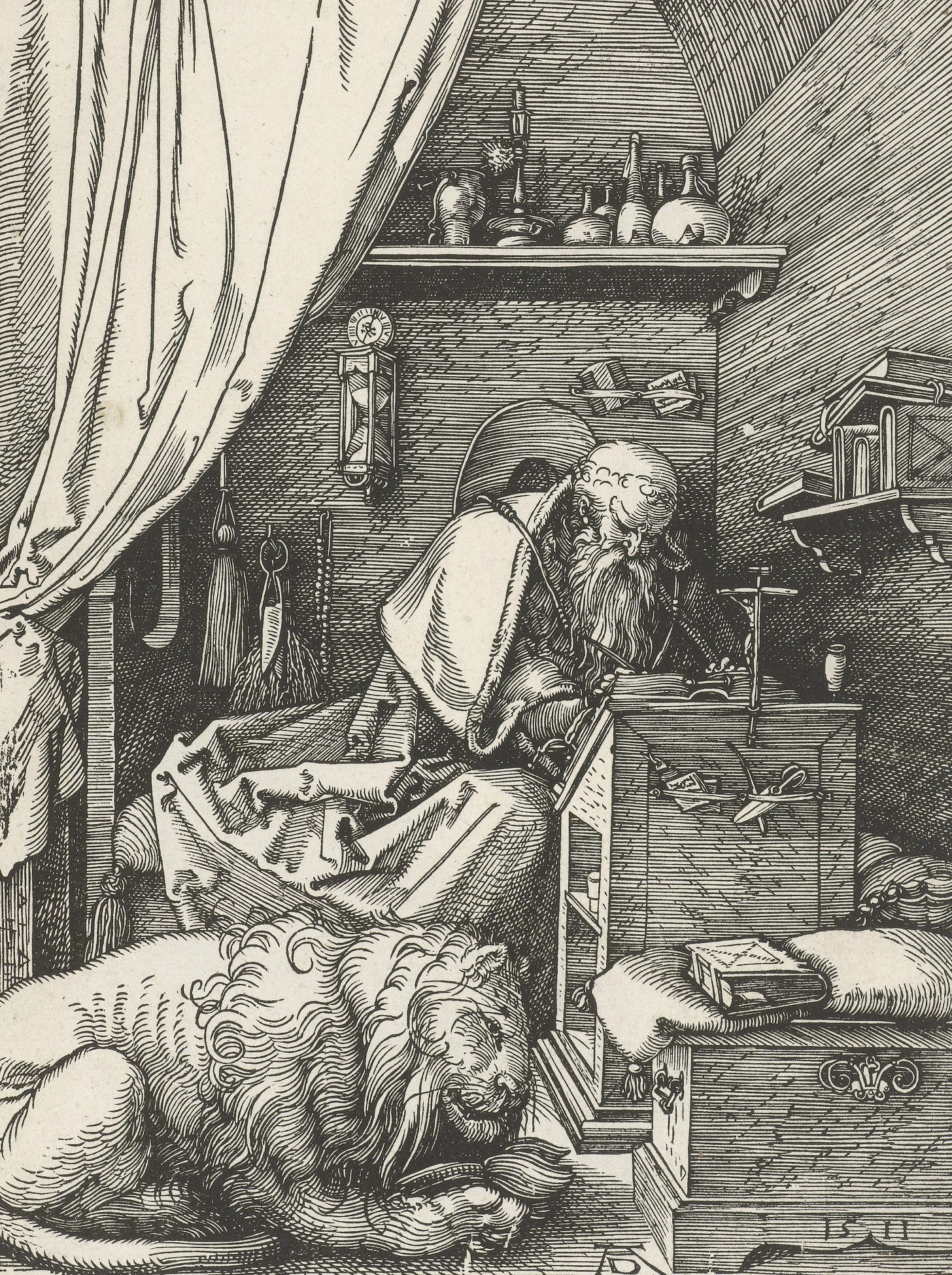

The top image is Saint Jermone in his Study, Albrecht Dürer, 1511

The black and white photographs are from the U.S. Forest Service- Pacific Northwest Region, circle 1920-1950

"Contemplate" is "with-time-ize" etymologically...the root of the metaphor here (and most words are metaphors, and most of the roots have been lost to most people) suggests investing time into something, even if you are "merely" looking at it. Lovely post.

Simon, I am really fond of you writings. Keep it up!