Designing a New Old Home series, Table of Contents

Beginnings — Why an “old” home, and how we came to buy land

Curiosity — Advice on starting

Research, Sketch, Collect ← You are here

Defining Constraints — What can we do without

The Elements — Heating and cooling and airflow

Materials and Hardware — What we built with

The Studio

The Kitchen

…

Essential Research for Home Design

In the first post I mentioned a few problems with new homes we wanted to avoid, centered around what’s dull or lazy about modern design. But beyond avoiding what is bad, you should think about how you can capture what is good about the traditional homes of your area.

Part of this is aesthetic. A classic New England home is considered classic because so many people have built in a consistent set of patterns. A house should feel like it is from somewhere — and this is only possible if the house and the land adorn each-other. Building something traditional contributes to the landscape, and we should take this seriously. Places exert themselves on us, they twist and turn our moods. The land shapes us as we shape it.

On the practical level, you should study the vernacular architecture of your area to search for good building practices. Traditional architecture, like most tradition, is a creation born out of managing unseen and unstated trade-offs and consequences, often for generations. Sometimes important features are not obvious until they are removed, and can only be fixed with great expense, or not fixed at all.

Many old home features are a response to the environment. A simple example: large porches especially in the southern US are meant to shade windows from excessive sunlight and heat, while south-facing houses in the north are meant to capture it. A well-designed porch may let in sunlight only in the winter time, when the sun’s pitch is low, and well-placed trees may provide sun cover in the summer and sunlight in the colder months, once their leaves have fallen.

Old houses tended to face a certain way, and while they may be contending with different pressures, the layout is almost never an accident. We want to be equally careful with our own building. House orientation extends beyond the buildings themselves: You want to be sure any porches or patios are in pleasing locations, and if you intend to keep a dooryard garden or kitchen garden, you’ll want to make sure it is properly positioned. For example, here in New Hampshire it is ideal for a kitchen/dooryard garden to be close to the kitchen of course. But it should also receive ample southern sun exposure, and ideally be protected from cold north or westerly winds, which may destroy early plantings that are sensitive to frosts. It would therefore be very inappropriate to have this dooryard (which contains a garden) on the other side of this house, even though its the same distance from the kitchen:

You will find many building- and region-specific examples of architecture and details, and it’s good to know why people did certain things so that you can decide if it’s something you want to do or avoid. In addition to functional cues, you might also get an essential grasp of why certain styles and fashions developed.

I was going to include a few more vernacular architecture examples in my final edit here, but I’m near the email length limit for this post! So perhaps I’ll give more examples in a later post.

Read (that’s part of research)

If you’re going to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to build something, I suggest you take this step seriously.

At a minimum you should read two books. The first is Get Your House Right: Architectural Elements to Use & Avoid by Marianne Cusato with illustrations by Richard Sammons and Leon Krier. It is a thoughtful book, illustrating in a “Use X — Avoid Y” fashion how to reason about appropriate features and patterns. It is the best of its kind that I’ve found.

There’s a lot of detail in Get Your House Right, which can seem intimidating. Some of these details are less important, I think, than the proportions and the level of honesty that you put into your design. It is perfectly OK to build a grand house or a simple house, but a simple house should have simple features, and not exaggerated ones. When houses look bad, it is often because things are out of proportion or scale. Cusato’s book is a great introduction to thinking about this. I’ll come back to this concept of honesty later, because I think it is essential for getting things right in any budget.

It’s not an essential read, but Leon Krier also has a book of just his illustrations called Drawing for Architecture which explains intuitively the differences between—in his opinion—good and bad architectural patterns, city planning, and living for that matter. You do not need Krier’s illustrations to design a house, but understanding his thinking may help you to think about housing, and I think his commentary-by-drawing is worthwhile.

How was it possible that any simple farmer could make a house, a thousand times more beautiful than all the struggling architects of the last fifty years could do?

Or — still simpler — how, for instance, could he make a barn? What is it that an individual farmer did, when he decided to build a barn, that made his barn a member of this family of barns, similar to hundreds of other barns, yet nevertheless unique?

The proper answer to the question … lies in the fact that every barn is made of patterns.

— Christopher Alexander, The Timeless Way of Building

The second book you should read is The Timeless Way of Building by Christopher Alexander. Alexander proposes that our intuitive love of many beautiful places rests on a certain quality that remains nameless. While it may be hard to define, it is easy to notice, and you have no doubt encountered it in beautiful cottages, gardens, temples, ancient city centers, and other places. The quality makes a place feel so natural we almost forget that these places were the careful and deliberate work of people.

Alexander wants us to work towards making these quality places, and sets about describing what he calls a pattern language for doing so. As I said before, beautiful places do not repeat identically the world over, but they do rhyme. There are patterns that make a place beautiful, not only in the design itself, but in the things that repeatedly happen there. When you design a restaurant or a breakfast nook, you are not just designing part of a building, but designing a place where people can enact rituals.

The aim of The Timeless Way of Building is to introduce these patterns and to give a clearer description of the things we intuitively consider important about our environments, but may have never verbalized before. I actually find his writing style a little silly, but the concepts are so important that I recommend this book to almost anyone interested in creating a beautiful and meaningful place, home or otherwise.

There are lots of other books worth reading, but the worst thing you could do is go buy a stack of books and then read none of them. Finish these first.

After that, you should probably look for a few books about architecture in your area. A great example for New England is Big House, Little House, Back House, Barn: The Connected Farm Buildings of New England. It is extremely well-researched, and in supporting its central question (why did people build the way that they did), it offers a lot of insight that might help you plan and position the masses of your home. You are not a homesteading farmer from the 1800’s, but you do use the rooms of your house in repeatable ways, and you should give as much thought to your daily use and patterns as these settlers did when designing their own home layouts.

Unfortunately, I think the book A Field Guide to American Houses is not particularly worth buying. It’s large, but surprisingly light on detail, and missing styles (such as the traditional New England saltbox). Better to find a book more focused on your area.

Starting the Designs: Sketch and Copy

I recommend you draw and sketch a lot — until you feel very comfortable doing it. Sketch facades freeform, with the ruler, etc. Sketching from photos is much easier than sketching from your mind, so you may want to start there. If you have any beloved houses from your childhood, you should try to sketch out their facades and floorplans from memory, too. The more houses you sketch, the more you will notice some patterns feel intuitively right about their design.

I suggest you start designing by copying existing designs and floor plans, if you have some that you like, and trying to modify them. It is almost always easier to begin with an existing good design, and think about how you can adapt it to your own needs and land conditions, than trying to start from a purely abstract blank slate. Many excellent homes are traditional, and all traditional homes are derivative. Whenever possible, you should build upon the careful thought of others.

We often have several of different sizes of sketchbook and notepad laying around, though I prefer the brands with dot-grids.

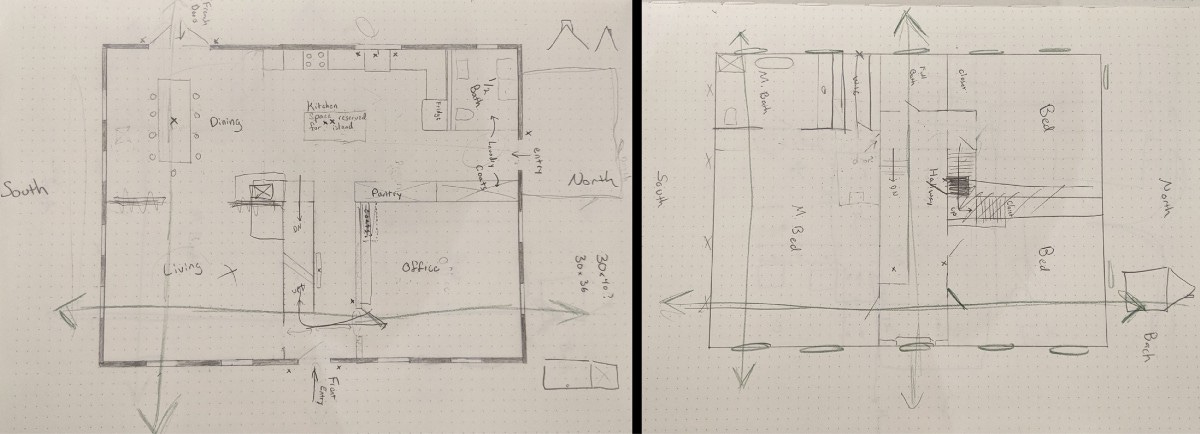

If you don’t have land yet, you probably shouldn’t be married to a particular design. Not all building pockets are flat, and the orientation of the house may be affected by other things, such as the road, especially if it requires a short driveway. Without knowing these, its difficult to know which direction the sun will be coming from, what windows might overlook the backyard or neighbors house, and so on. Your final design should not be a paper abstraction, but should feel intimately tied to the surrounding land.

Once the house design is finalized and construction begins, you’ll want to continue sketching, this time for landscape design. If you choose to pay for landscaping (we didn’t), you’ll probably want a basic design done by the time the construction is finished. If you’re like us, you’ll be designing and landscaping for the next 5 years. Or more.

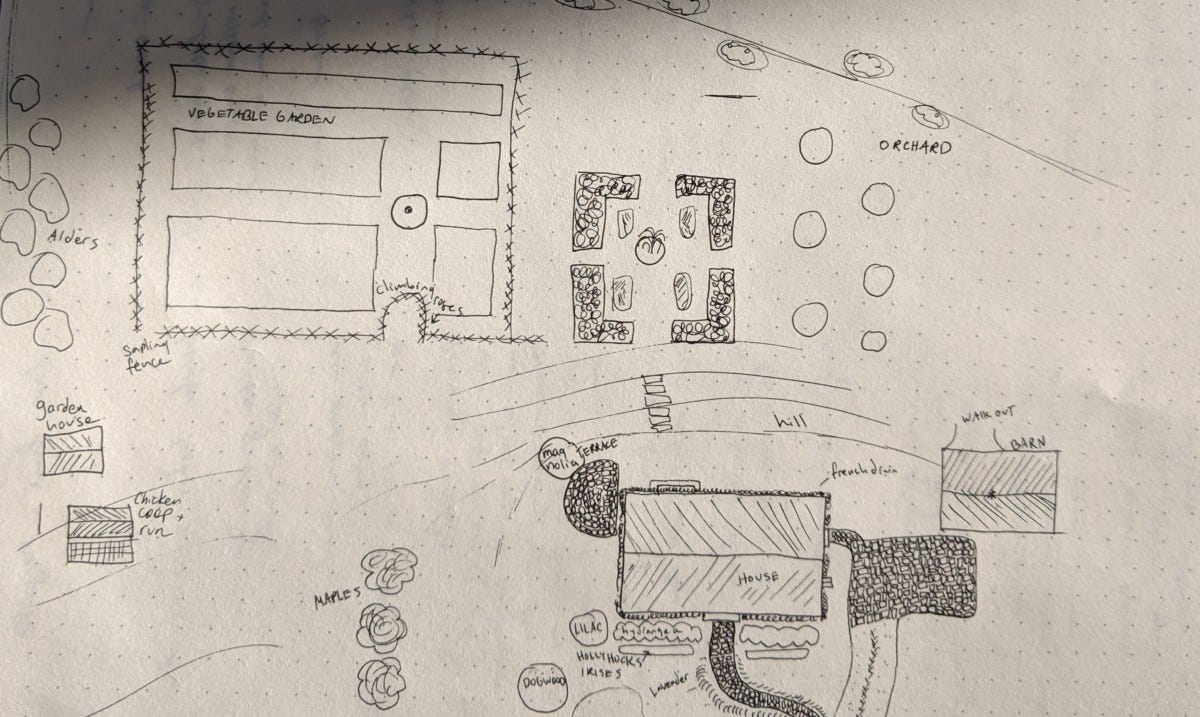

An early garden plan:

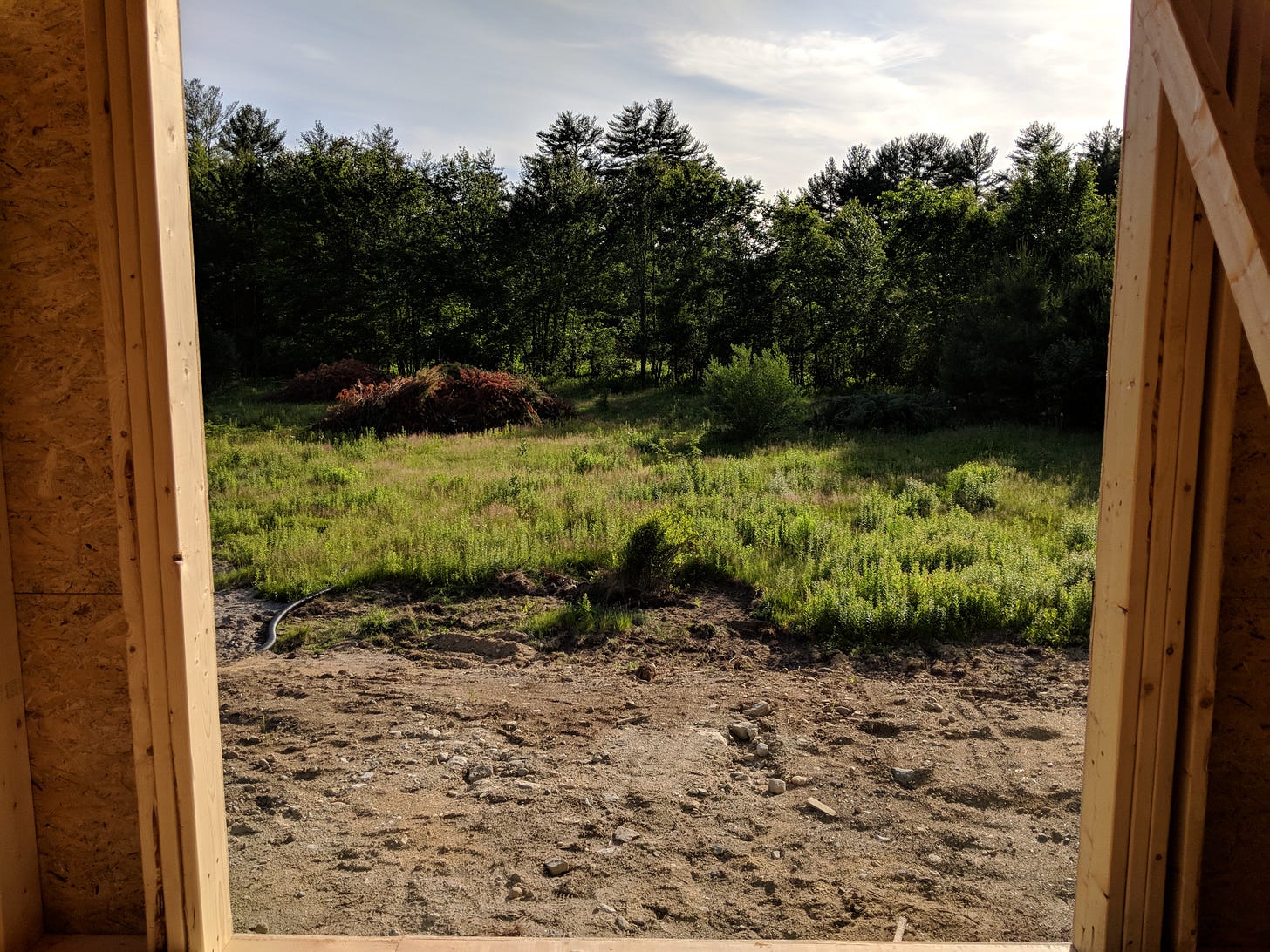

An early scene, viewed from the house’s back doors, 2018:

And early July 2022. This year’s drought was starting to wear on things. We planted the sugar maple and plane tree (bottom of picture), lilacs, a magnolia, and some other things from original plans. The chicken coop from our plan is also present, but hidden behind a large autumn olive tree, near the upper left. And a barn (the Goose Palace) is present too, but a bit farther from the house than our sketch, and hidden in this photo:

Collect

If you have a good idea of what you want to build, you can start buying fixtures long before you break ground. Also, visiting some architectural salvage stores in your area early might help you to get ideas.

There are a number of sites that sell interesting house hardware, parts like cabinet pulls, doorknobs, light fixtures, tile, door knockers, and other details. If you find any you like, sign up for email promotions, and you may find sites that routinely offer 20% or more off sales. With a little planning, you can sign up for them and wait for the next sale. Some sites have big sales only one or two times a year, so it pays to consider what hardware you want fairly early in the process. The place where this might really matter are for water and light fixtures, and tile manufacturers (we used a lot from Cle Tile). You could save thousands in tile and shipping costs by timing a sale.

Note that some sites, like House of Antique Hardware, are often just reselling other brands with a markup. For example the fairly standard brass cabinet pulls on their site are actually just Emtek brand pulls, which you can get for cheaper from sites like build.com.

Buying pulls and knobs sold as lots on eBay is sometimes cheaper than sale prices. If you find expensive knobs you like on one site, go to eBay and search the product name.

Retail isn’t the only place to find fixtures of course. To add to the old feel of our house, we bought some antique and architectural salvage lights and hardware, which you’ll see in the post on materials. For this eBay, Etsy, yard sales, Facebook Marketplace, Craigslist, and architectural salvage companies (There are a lot in New England) are easy sources.

In the next post we’ll go over the elements, heating and cooling, and how these affect our design. Or it will be about materials and hardware, if I get to that first. My daughter was born on August 12th, so I may be a bit delayed in writing for a while. This post was mostly finished before then, and I only now edit it, in the mild delirium of newborn nights.

This newsletter is called The Map Is Mostly Water, and is about a number of topics.

This house design post is part of a series inside that newsletter, called Everyday Aesthetics.