Careful technology

Dear friends,

There is a commonplace opinion that technology and the natural world, or that technological pursuits and natural pursuits, are at odds. An example:

I think this is a false position. But if this kind of sentiment is so often repeated, its worth thinking about why it feels true.

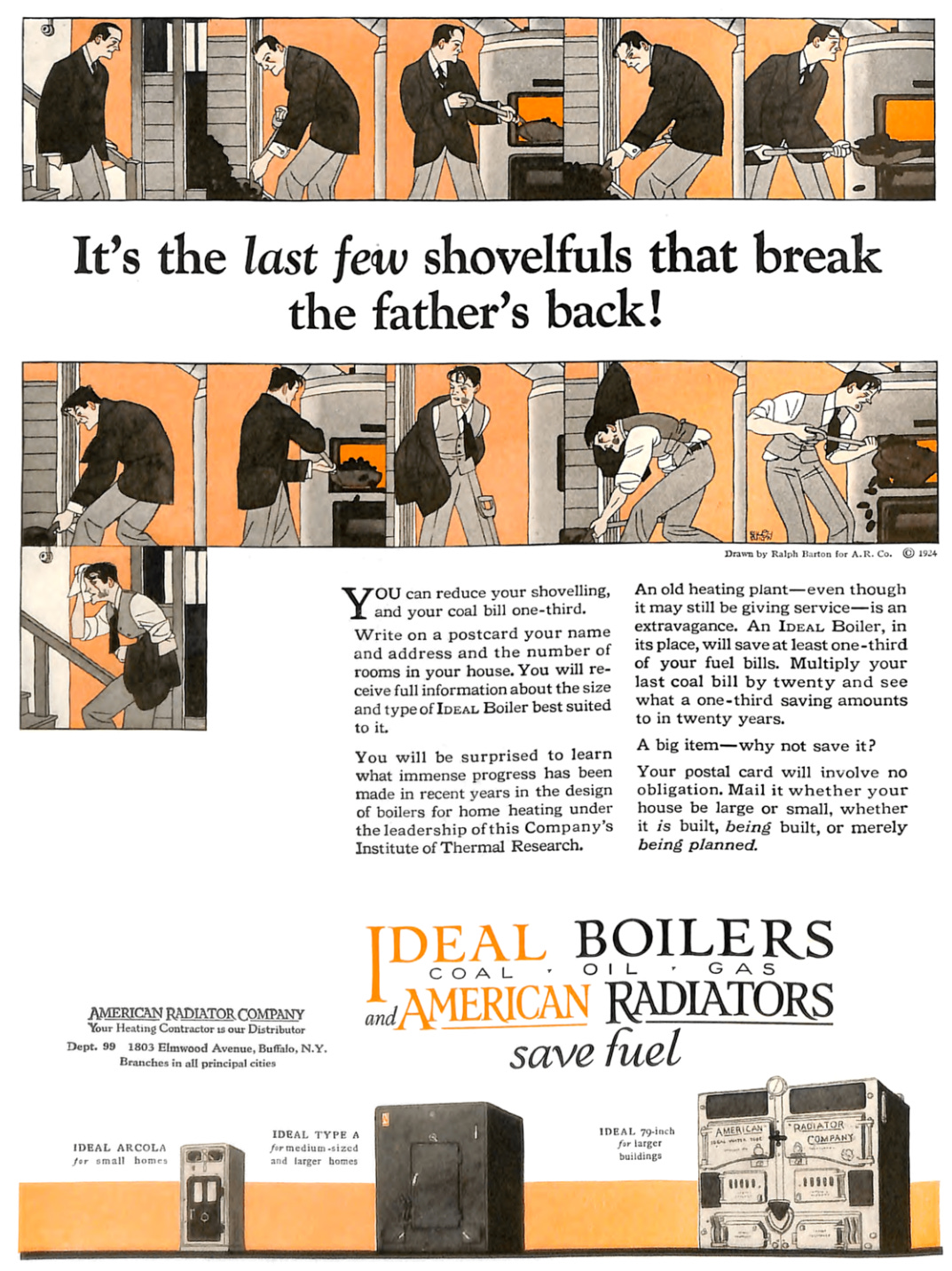

Technology is doing more with less. This is a definition we should not lose sight of. The wheel allows one to move more weight, or with less effort. The gas boiler allows heating with less labor than coal. Email is faster and cheaper than postal mail. There are other tradeoffs made of course, we’ll get to that.

I suspect the essential reason why people think that technology clashes with nature has little to do with technology per se, and possibly little to do with nature. Instead the trouble is that so much of what’s called technology feels frustratingly careless. Consider the category of Smart Home Devices:

We should first ask ourselves: what do any of these smart home devices have to do with the idea of Home? If you were asked to come up with words that evoked the ideal home1, I would be surprised if they described any of the objects above, in function or design.

These devices strike me as mostly careless. They often have a pretext of technology, of getting more-for-less, but I think this is a false economy. If you buy a Smart Lightbulb and have to concern yourself with device pairing, versions, updates, and buying only the same product now to match, you are making tradeoffs. You are getting more with more, you are trading your own time and effort to obtain the clever bulb.

Many modern devices (and apps) really excel at squishing tradeoffs into weird shapes. They are better thought of as little imps that sneak into homes and ask for more and more of your attention. They want to gently claw at your eyes and ears. They want to put notifications on your phone and remind you that you need to interact with them, or buy more of them, so that they might become even more convenient. This does sound miserable. This does sound contra-nature.

With enough of this stuff you are also trading away the cozier feeling of home. Possibly the convenience of some devices are worth it, but I think many technologies only have popularity because the tradeoffs made are not quite so clear as simpler technologies, like those that are merely trading money for time or physical work (like a tractor, a more efficient boiler, an airplane ticket, etc).

One machine epitomizes unusual tradeoffs: the Keurig coffee maker

Does it make coffee cheaper? No

Higher quality brew? No

Less maintenance? Also no

More ecological? Alas…

Healthier? You’re squirting boiling water through plastic

Prettier? It practically invented corporate chic — it is inviting a piece of the office lunchroom into your home

Is it faster? Yes. It is.

The Keurig machine can make one hot drink faster than most preparation methods. Along one axis it does more with less. But taken as a whole it strikes me as a strange trade — along so many axes it is a machine that does less with more. To me it exists as a kind of anti-technology.

Even when the tradeoffs are more clear, I think that technology has to feel humane and serve very human purposes to be worthwhile. Most gadgets feel careless and unwholesome and I worry that they, subconsciously, cause us to treat our homes differently. They are not viscerally pleasing, and if you have enough of that sort of thing in your home I think it lends to an air of unreality.

If people hate technology and think it clashes with nature, I find it hard to blame technology. We have careless technology because we are careless in evaluating it. We demand too little of it, or we are willing to sacrifice too much for too little in return.

I am reminded of a Tolstoy quote2 that has always struck me: “People try to do all sorts of clever and difficult things to improve life instead of doing the simplest, easiest thing—refusing to participate in activities that make life bad.” I take this advice to heart, and I think it generalizes well. If you are stuck in a mall food court with only bad food, and you are hungry, you could always just stay hungry.

~ ~ ~

I love technology, the removal of drudgery over the last 250 years is something we should all be more grateful for. It lets us appreciate nature more: we have more time, more travel, more food with less risk, less disease. It is easy to lose sight of just how much was gained so recently. Even the would-be homesteader who wants to grow their own food has had the experience completely transformed by the advent of refrigeration and freezing. It is now something people do for fun. And I think we should be grateful for the digital world, too, which after all lets me write to you in the first place, and share my own version of nature.

But I dislike gadgets. I own no TVs, internet-of-things devices, home automatons, etc. In my opinion objects should not beep or be filled with blinking LEDs. Though I built my own house, I don't own a microwave — it is simply not useful enough to justify the space or the ugliness. The stove is propane gas. I like candles. In winter we heat with firewood. Some of this is durability: these things work even when the power goes out (as it does a few times a year in this part of New Hampshire). They can do more, with less.

What is called tech — that is, what is new and digital — is not necessarily technology in any meaningful way. Often it is merely fashion. The blame cannot rest with the objects and apps, no matter how careless they are made. It is always only up to you to decide if you are getting more for less.

~ ~ ~

post script: I almost made this post entirely about heating systems through the years and tradeoffs made with each. Only the first image, the Ideal Boiler advertisement, remains of that draft. But maybe the technology, some of it quite elegant and careful, deserves its own follow-up post.

from Path of Life

I liked Wendell Berry’s standards for technological innovation. Hard to follow but good to measure any new technology against:

1. The new tool should be cheaper than the one it replaces.

2. It should be at least as small in scale as the one it replaces.

3. It should do work that is clearly and demonstrably better than the one it replaces.

4. It should use less energy than the one it replaces.

5. If possible, it should use some form of solar energy, such as that of the body.

6. It should be repairable by a person of ordinary intelligence, provided that he or she has the necessary tools.

7. It should be purchasable and repairable as near to home as possible.

8. It should come from a small, privately owned shop or store that will take it back for maintenance and repair.

9. It should not replace or disrupt anything good that already exists, and this includes family and community relationships.

Nature does not rush, yet everything gets done. Technology speeds up our activities. But we do not let a time savings create space in our days. Instead it is on to the next task, and the one after, and that is what feels unnatural.